Allied plan at the battle of Tourcoing, 17-18 May 1794

|

|

Introduction

The French Position

The Allied Plan

17 May

18 May

The battle of Tourcoing (17-18 May 1794) saw the failure of an over elaborate Allied plan designed by General Mack to annihilate the French Armée-du-Nord. At the start of the 1794 campaigning season the Allies had decided to besiege Landrecies, while the French decided to attack at both ends of the front line on the Franco-Belgian border. The attack on the left was the most successful. The Austrian General Clerfayt was defeated at Mouscron (29 April) and on the following day Menin was captured.

The Allies, then under the personal command of the Emperor Francis II of Austria, were forced to rush reinforcements west in an attempt to restore the situation. The French responded by attacking the Allied line twice in two days. The first attack (battle of Willems, 10 May 1794) ended in an Allied victory, but on the following day Clerfayt was forced to retreat north (battle of Courtrai, 11 May 1794), splitting the Allied army. The Duke of York, who had command of the Allied left, was forced to ask for reinforcements, and Francis and the Prince of Saxe-Coburg decided to concentrate their efforts in the west.

In mid-May the French had around 82,000 men in the area between Lille and Courtrai. Most of these troops, 28,000 men under General Souham and 22,000 under General Moreau, were on the southern banks of the Lys, between Courtrai and Aelbeke, to the north of the main thrust of the Allied attack. Another 20,000 men under General Bonnaud were at Sainghin, east of Lille, and General Osten had 10,000 men at Pont-à-Marque, to the south of the city. Other detachments were at Lannoy, Mouscron, Turcoing and guarding the main bridges across the Lys and the Marque.

General Karl Mack, notorious now for his defeat at Ulm, was responsible for the Allied plan at Tourcoing. His aim was to ensure the complete destruction of the French army, but his plan involved six separate columns attacking along a front of well over twenty miles, in difficult ground which made communication between the columns almost impossible. While Clerfayt at the right of the line was attempting to cross the Lys at Wervicq, west of Menin, the Archduke Charles would be crossing the Marque at Pont-à-Marque, south of Lille. As was often the case with Mack's plans, every column had to reach its targets if the plan was to succeed, and it took little account of any French reaction.

The main Allied attack was to come from the east. One column of 10,000 men, under Field Marshal Otto, was to advance through Leers and Wattrelos to Tourcoing. To Otto's left was the Duke of York, with twelve infantry battalions and ten cavalry squadron. The Duke was to advance through Lannoy to Mouvaux. To Otto's right was a small column of 4,000 Hanoverians under General Bussche, who was to march to Mouscron via Dottignies, while also sending a third of his force up the road from Tournai to Courtrai.

The Allied right wing was made up of a column under Field Marshal Clerfait. He was to start at Oyghem on the Lys, march along the northern bank of the river and cross it at Wervicq, west of Menin. Once across the river he was to advance south, behind Mouscron and Tourcoing.

The Allied left wing was to head to two of the bridges across the River Marque, which curved around the southern part of the battlefield, separating Lille from Tourcoing. Ten infantry battalions and sixteen squadrons of cavalry (9,000 men) under Count Kinsky was to advance to the bridge at Bouvines (between Sainghin and Cysoing, south east of Lille) and cross the river. He was then to wait for the sixth column, seventeen battalions and thirty-two squadrons (14,000 men) under the Archduke Charles, which was to cross the river at Pont-à-Marque, south of Lille and advance north to join Kinsky. The combined column was then to march north to join the Duke of York at Mouvaux.

Mack's plan quickly unravelled. At the far right Clerfayt reached Wervicq, on the Lys, on the afternoon of 17 May, only to find the bridge fortified and defended in strength. He would not cross the river until the following morning. Next in line was Bussche. He successfully reached Mouscron, but was then driven back to Dottignies by a heavy French counter attack.

On the Allied left Kinsky reached Bouvines, but was unable to prevent the French from destroying the bridge. The Archduke Charles's advance was very slow. His column finally crossed the Marque at two in the afternoon, and then halted at Lesquin, four miles north of Pont-à-Marque, but well short of his objective for the day.

In the centre General Otto reached Tourcoing, but was out of touch with the Duke of York to his left. The Duke's first advance reached Roubaix, two miles east of Mouvaux, where the Brigade of Guards forced the French to abandon a strongly held position. The Duke was unaware of Otto's success to his right, while the columns to his left had made no progress. Worried that he might be dangerously isolated, the Duke decided to withdraw slightly, to Lannoy, but the Emperor overruled this plan, and ordered him to continue with the advance as planned. The Guards repeated their success at Roubaix, and at the end of the day the Duke of York's column camped on the road between Roubaix and Mouvaux.

At the end of 17 May the Allied plan had clearly failed. The Duke of York and Otto had reached their targets, but the columns on the right and left had all failed. That night the senior French generals held a council of war (Pichegue was then absent from the army). Souham, Moreau, Macdonald and Reynier met at Menin, to the north of the main Allied positions, and put in place a plan for a counterattack on the following day.

The French left wing lined up to the south of the Lys, facing south with their advanced guard at Mouscron. The French right wing spent the night just east of Lille. The plan was for Bonnaud's division from the right wing to attack north east towards Lannoy and Roubaix, while the left wing attacked south towards Mouvaux, Turcoing, Watrelos and Dottignies. The two central Allied columns, under Otto and the Duke of York, were in real danger of being annihilated by forces three times larger than their own.

On the morning of 18 May Otto's column was spread out across five miles, with seven and a half battalions at Tourcoing, two at Wattrelos and three at Leers. The Duke of York's column was equally stretched. The Guards Brigade was at Mouvaux, four Austrian infantry battalions and the Sixteenth Light Dragoons were at Roubaix, three British battalions were guarding his left flank on the road from Roubaix to Lille. Two more battalions were in the rear at Lannoy. Between them Otto and the Duke of York had around 18,000 men at six main positions. They were about to be attacked by around 60,000 French soldiers.

Otto's advanced position at Tourcoing was hit first. The Duke of York sent reinforcements north in an attempt to hold the position, but arrived too late to prevent the French from capturing the town. The French also captured Wattrelos, but Otto's column was able to escape along a minor road south of that position.

The Duke of York was in the most danger at Mouvaux. At around seven in the morning Bonnaud's columns reached Roubaix and Lannoy, while part of his division advanced towards Mouvaux. A short time later General Malbrancq's brigade attacked Mouvaux from the north, and was soon supported by part of the column that had captured Tourcoing.

The British were soon split in two by the advancing French. The Brigade of Guards (Abercromby) was isolated at Mauvaux, while the Brigade of the Line, under Major-General Fox, at Croix (to the south east). Part of Bonnaud's division, coming from the south, had reached Le Fresnoy (between Mauvaux and Roubaix), while Thierry and Daendel's brigades were advancing towards Roubaix from the north. The Duke of York himself was isolated at Roubaix with part of the Sixteenth Light Dragoons. After attempting to reach Abercromby and Fox, the Duke was forced to head for Wattrelos, where he hoped to find General Otto. Instead all he found were more French troops, and only just escaped capture.

The two British brigades were forced to fight their way out. Fox and the Line Brigade managed to reach the road at Lannoys, and made some progress along it before running into a newly built French abatis. Only the help of a French émigrés allowed Fox to eventually reach safety at Leers, with the loss of 534 of his original 1,120 men.

The Brigade of Guards began its retreat at around nine in the morning. At Roubaix it briefly descended into chaos after the artillery horses were let loose as their drivers fled, but the Guards managed to restore order and continue on towards Lannoy. On their arrival there, the British believed the town to have fallen to the French, although it may still have been held by a force of Hessians. Believing Lannoy to be in French hands, the Guards then turned south-east and headed across country to Marquain (just west of Tournai). By the time they reached safety the Guards had lost 196 men, out of the total of 930 British casualties suffered during the battle.

Elsewhere the remaining Allied columns were largely inactive. Clerfayt finally crossed the Lys then turned east, and clashed with Vandamme's brigade. After defeating this force, which he outnumbered by two-to-one, Clerfayt was threatened by the arrival of more French troops and retired behind the Lys. Bussche and his small column of Hessians held their position at Dottignies, but could do little else.

On the Allied left Kinsky and the Archduke Charles were remarkably inactive. The Archduke was sent orders to move to Lannoy early in the day, but the march did not begin until noon. At three the Austrians finally reached the road from Tournai to Lille, still some way south of Lannoy, and were then ordered to retreat to Tournai. A variety of reasons for this slow progress have been put forward, amongst them deliberate sabotage of Mack's plan by an Austrian rival in the staff, or a desire to abandon the war in western Flanders, none of which entirely convince. Although the Archduke Charles would later win an impressive reputation as a general, in 1794 he was only 23, and had yet to learn his craft. Inexperience seems a rather better explaination that some of the more elaborate conspiracies.

The fighting ended at around half past four, when the French called off their attack. The Allies had lost between 3,000 and 5,500 men and 50 guns. French losses were lower, at around 3,000 killed and wounded. The battle was a clear French victory. The Allied plan had completely failed, and the Austrians would soon begin to lose interest in the fighting in western Flanders. The battle is sometimes inaccurately described as inconclusive, probably because the French missed their chance to crush Otto and the Duke of York's columns on 18 May. After Tourcoing the French went onto the offensive, but their attack on Tournai (22 May 1794) also ended in failure. The focus of the campaign then moved east, to the Sambre, where the French repeatedly threatened Charleroi.

The Duke of York’s Flanders Campaign – Fighting the French Revolution, 1793-1795, Steve Brown.

Looks at the Flanders campaigns of the War of the First Coalition, the first major British involvement in the Revolutionary Wars and the campaigns in which the ‘old style’ Eighteenth Century armies and leadership of the Coalition proved lacking when faced with the new armies of Revolutionary France. Focuses on the British (and hired German) contribution, and the role of the young Duke of York, whose Royal status gave him a command that his military experience didn’t justify (Read Full Review)

The Duke of York’s Flanders Campaign – Fighting the French Revolution, 1793-1795, Steve Brown.

Looks at the Flanders campaigns of the War of the First Coalition, the first major British involvement in the Revolutionary Wars and the campaigns in which the ‘old style’ Eighteenth Century armies and leadership of the Coalition proved lacking when faced with the new armies of Revolutionary France. Focuses on the British (and hired German) contribution, and the role of the young Duke of York, whose Royal status gave him a command that his military experience didn’t justify (Read Full Review)

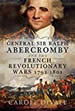

General Sir Ralph Abercromby and the French Revolutionary Wars, 1792-1801, Carole Divall.

A biography of one of the more competent British generals of the Revolutionary Wars, killed at the height of his success during the expulsion of the French from Egypt. Inevitably most of his experiences during the Revolutionary War came during the unsuccessful campaigns in northern Europe, but he managed to emerge from these campaigns with his reputation largely intact, and won fame with his death during a successful campaign. An interesting study of a less familiar part of the British struggle against revolutionary France

(Read Full Review)

General Sir Ralph Abercromby and the French Revolutionary Wars, 1792-1801, Carole Divall.

A biography of one of the more competent British generals of the Revolutionary Wars, killed at the height of his success during the expulsion of the French from Egypt. Inevitably most of his experiences during the Revolutionary War came during the unsuccessful campaigns in northern Europe, but he managed to emerge from these campaigns with his reputation largely intact, and won fame with his death during a successful campaign. An interesting study of a less familiar part of the British struggle against revolutionary France

(Read Full Review)